am I experiencing comphet or am I a bisexual attracted to a golden retriever boy?

analysis of the intersection between compulsory heterosexuality and bisexuality

before we begin

Happy Pride Month!

This month on the Substack, I wanted to gather my jumbled thoughts and shape them into something more cohesive. One of my favorite things about writing here is how it helps me reflect, untangle, and figure out where I stand on things.

As someone who only semi-recently began embracing the label “bisexual,” this reflection feels especially meaningful. That said, this post is mostly personal: it includes some definitions, yes, but it’s rooted in opinion, lived experience, and the ever-evolving process of figuring myself out. I’m still just scratching the surface of what it means to be queer—especially while in a relationship that, on the outside, looks heteronormative.

So grab a little drink, maybe a snack, and let’s dive in.

I started to unravel my sexuality the summer I realized I was crushing on my best friend.

We were long-distance, texting constantly, sending each other playlists and paragraphs that straddled the line between casual and intimate*. I’d reread her messages late at night, my heart fluttering at a well-placed emoji or a compliment that felt like it meant more.

And yet, at the same time, I was joyriding with a sweet, goofy boy who gave “golden retriever” energy in every possible way. I liked him—or at least, I thought I did. But something didn’t feel right. That was when the questions began:

Am I into her? Am I into him? What will my parents think?

This was my introduction to the messy, overlapping territory of compulsory heterosexuality and bisexuality—where attraction, expectation, and identity all blur together.

*It wasn’t until recently that I came across the term “homoerotic” and so many things make so much more sense now. Another future Substack post might be in the works regarding this topic, friend.

compulsory heterosexuality (aka comphet)

One of the highlights of last summer (for me) was watching Chappell Roan’s Good Luck, Babe! blow up. I loved analyzing the lyrics and deep-diving into online theories. At some point, I saw someone say the song was about “comphet,” and I knew I had to look into it.

Compulsory heterosexuality, or comphet, is the pressure—often invisible but always insistent—to conform to heterosexual norms and expectations, even if your true orientation or gender identity is something different.

If that resonates, take a second to let it sink in. For me, learning that term opened up a whole new perspective. It was like finding the missing puzzle piece. So many things suddenly made sense.

But to talk about my experience with comphet, I need to also talk about…

religion

I grew up in a conservative Christian household. Aspects of this included firm gender roles, so much focus on purity culture, and talk of “spiritual warfare” (everyday struggles, especially doubts or desires that don’t align with Biblical teachings, were interpreted as attacks from Satan or spiritual weakness).

Oh, and shame. Lots of shame.

I've spent a lot of time in therapy unpacking the ways religion shaped me—for better or worse. The short version? Growing up, I internalized a lot of homophobia.

Actually, it started as pure homophobia. Because until I was about 15 and started wondering if I might be “a little fruity,” I was fully the kid parroting the things I heard in church. Like:

“Hate the sin, not the sinner.”

“You can have same-sex attraction, just don’t act on it.”

“God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.”

(Yeah. The cringe is real.)

And then one day, I realized I was the “sinner.”

Cue the internalized homophobia. I was already navigating undiagnosed social anxiety, and now I got to add on the shame, self-loathing, and fragile sense of self-worth that comes with realizing you’re gay—and that your parents may never accept it.

…Whoo.

circling back

Fast-forwarding to the point where my anxiety was medicated and my mental health was officially stable.

In the summer of 2023, freshly graduated from graduate school, I felt like I was finally able to step back and look at myself. Under the surface, I’d been thinking about my identity for a while. But it wasn’t until that summer that I felt comfortable enough to say to myself, and eventually my friends:

I am bisexual.

bisexuality

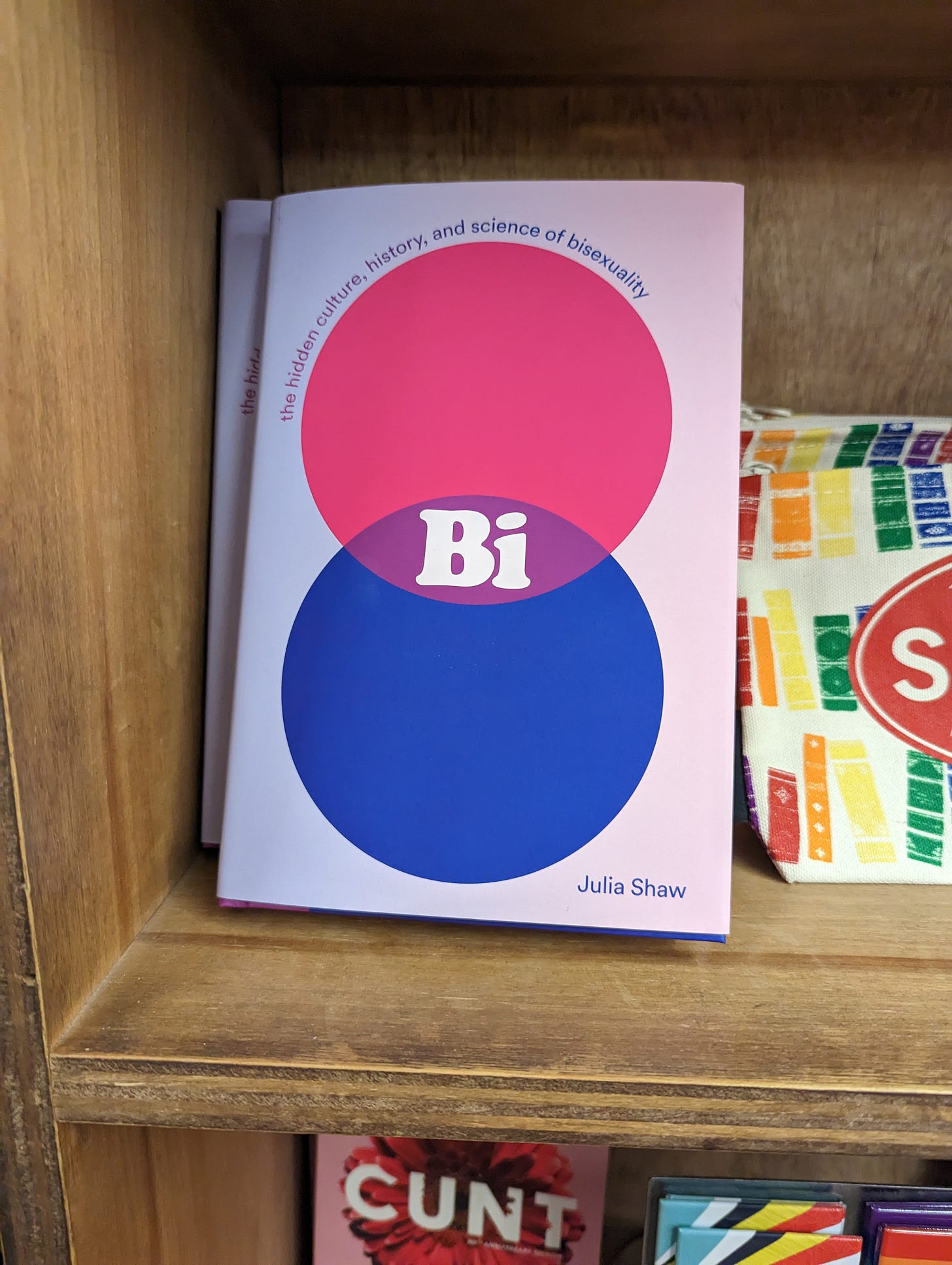

My absolute favorite explanation of bisexuality comes from Julia Shaw and her book, “Bi: The Hidden Culture, History, and Science of Bisexuality”:

In the etymology of Kertbeny’s “heterosexual,” “hetero” comes from the Greek heteros which means another, while homos means same, and both are melded with the Latin word sexus. Not long after this, bi, or two, started to be used to refer to people who had both homosexual and heterosexual desires. A way that bisexual researchers often talk about this is that the bi in bisexual means two, but the two are not men and women, they are same and other.

I love this quote because it describes my identity so perfectly. I’ve been corrected by others on what it means to be bisexual, but I think you’re allowed to take a label and make it your own.

So where does comphet come in?

comphet & being bi: confusion on top of confusion

Comphet often creates a deep sense of confusion—especially for bisexual individuals—by making them question their attraction to different genders. It can cause doubts to surface around what is genuine desire versus what has been shaped by societal or familial expectations.

I’ve seen this most clearly in conversations where certain relationships are subtly (or not-so-subtly) devalued. Take, for example, the common phrase: “Most bi women end up with men.” That kind of framing implies that choosing a man is either inevitable or less meaningful, and it can erase the complexity of bisexual identity altogether.

For me, the confusion stemmed from wondering whether I was with my current male partner because that’s what I genuinely wanted—or because it felt like the safer, more socially acceptable choice. Especially when I was younger and still deeply immersed in the values and beliefs of my family, being with a man felt like assimilating—like following the path of least resistance, even if it didn’t feel fully right.

the truth of the matter

Looking back, I’ve known I was attracted to women since I was 15. That summer, I found myself completely captivated by my best friend—the same one who breadcrumbed me and (let’s be honest) lied, ha. Even in the confusion and heartbreak of that situation, the feelings I had for her were real. They weren’t a phase, or a projection, or the result of being “too close.” They were desire and longing and curiosity—and deep down, I knew it. For years, though, I buried that truth beneath layers of doubt, religious guilt, and the easy assumption that I would “end up with a guy” anyway.

But now, after years of untangling all that noise, I’ve found pride and grounding in the labels queer and bisexual. They feel expansive enough to hold all the complexity of my experience—attraction that doesn’t fit neatly into boxes, a self that continues to unfold, and a love for identity that is fluid, but no less real.

Something else I’ve come to accept is this: the fact that I feel attraction to more than one gender doesn’t make my love for my male partner any less real. And being in a relationship that looks straight from the outside doesn’t make me any less queer. For a long time, I worried that identifying as bisexual while being with a man somehow invalidated my queerness—as if my identity had to be “visible” to be legitimate (I will no longer be part of my own bi erasure!). But queerness isn’t something you owe proof of. It’s something you are. And I am.

this one was cathartic to write

I don’t have all the answers. And for the first time, I can honestly say that I feel content with that. I love that I am still learning, I’m taking action to shed old beliefs and find language for what I’ve always known deep down. But every time I let go of shame and reach for truth instead, I feel more like myself. And that’s something worth celebrating.

If any of this resonates with you—if you’ve ever wondered if your queerness “counts” or if your identity needs to look a certain way to be real—let me be clear: it does. You do. You’re not alone in the confusion, and you’re not alone in the clarity either. There’s space for you here, exactly as you are.

Until next time,